The life-span of a tooth

Clinical outcomes and accelerated consequences of Teeth Grinding

Teeth grinding (bruxism parafunction) applies excessive force to a tooth, accelerating and intensifying the consequences highlighted below.

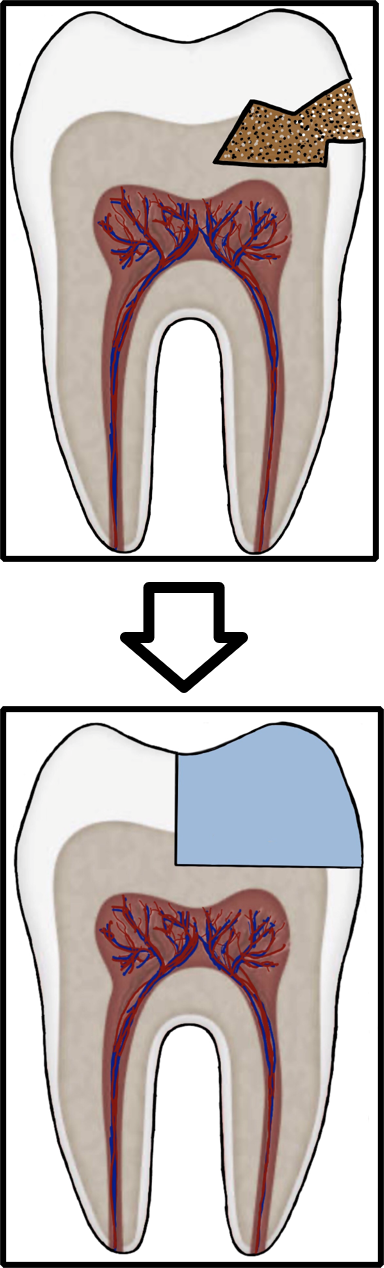

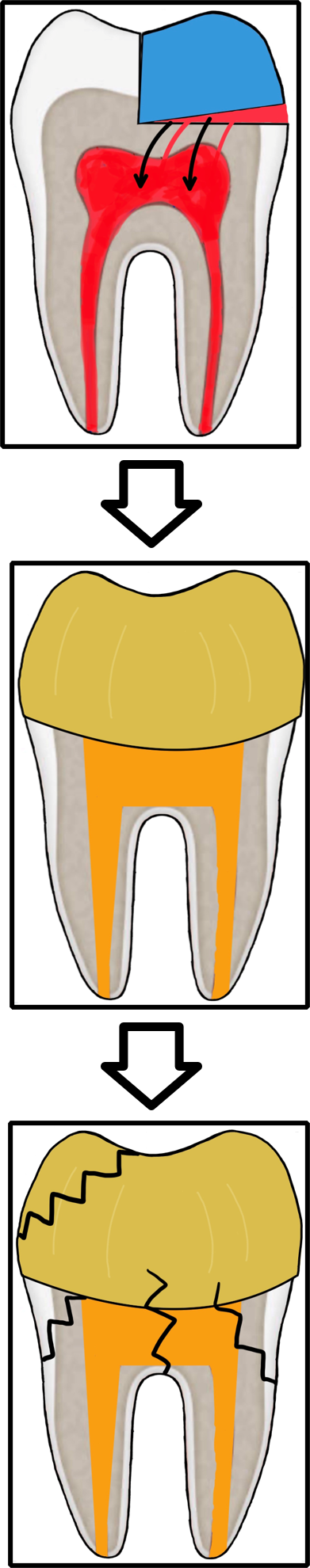

Secondary caries ( and eventually pulpitis) caused by Peripheral Rim Fractures (PRF) and marginal defects are common in teeth treated with traditional filling designs and bonding techniques. This occurs due to improper force distribution, especially during occlusal loading [1]. .

These forces, which typically range from 20-600 N depending on the tooth (incisors to molars), are intermittent, occurring primarily during chewing [2,3].

However, bruxers may generate forces exceeding 1000 N [2,3], and these forces are often constant or semi-constant in nature.

As a result, these patients are more likely to experience complications related to PRF much sooner, while restorative treatments like crowns or simple restorations are commonly used, they often fail to address the root cause that Biomimetic dentistry aims to solve—the microcrack.

Providing patients with a safeguard, especially those with evidence of tooth wear (BEWE) is crucial for extending the lifespan of their teeth. A dental appliance such as a night guard or Essix retainer is an excellent choice for distributing occlusal load more evenly across the teeth

Current literature suggests that although occlusal splints can reduce mechanical stress on teeth and lower the likelihood of further restorative treatments, their ability to address the root cause of bruxism - remains uncertain, regardless of material or design [3, 4, 5].

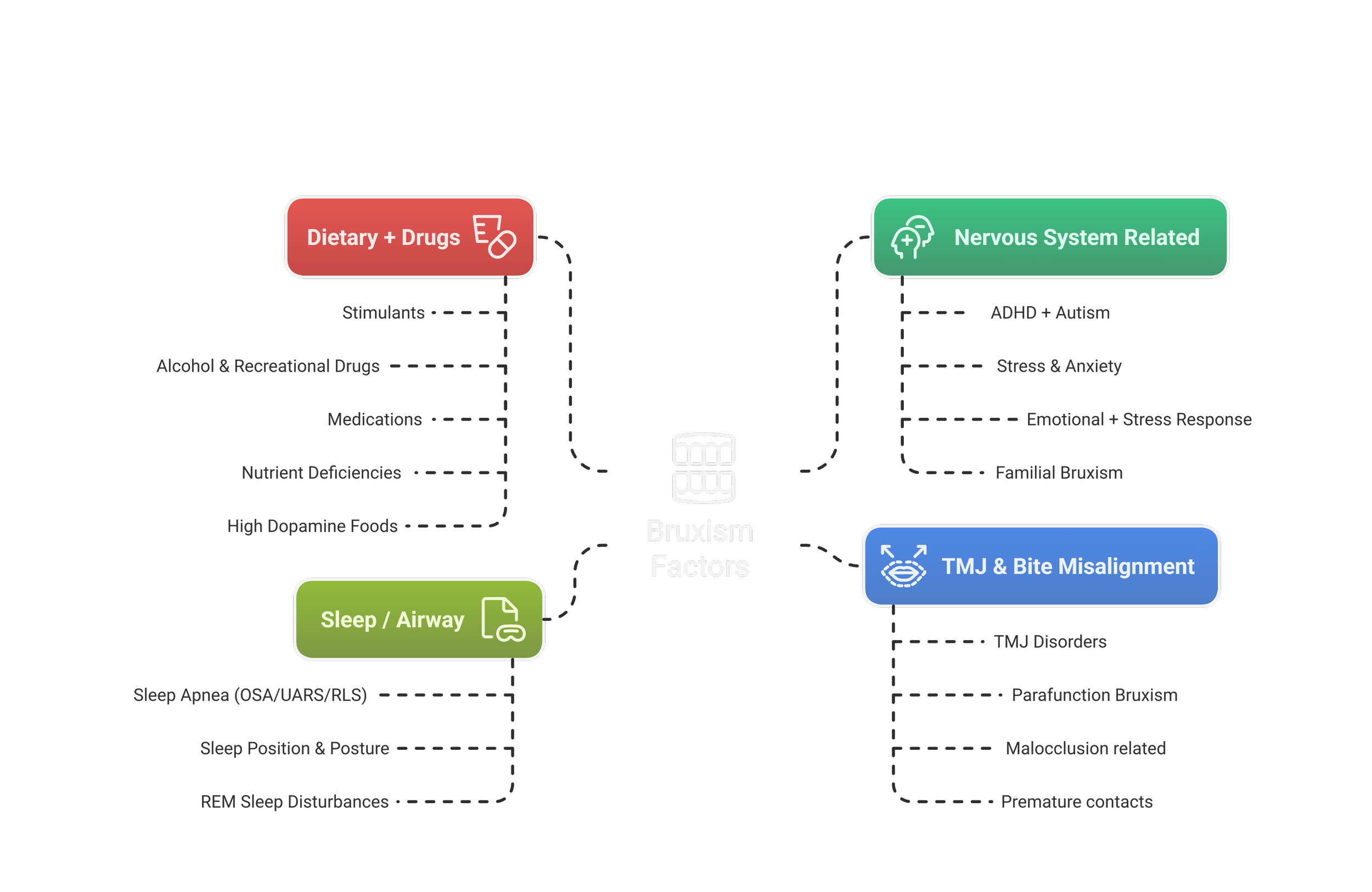

That is because they fail to address the physiological mechanisms behind bruxism: what is generating sustained motor output to the masticatory muscles, forcing the jaw to clench? Although some of it is habitual, dysregulated autonomic and neuromuscular activity, driven by an overactive nervous system, is the root cause.

[1] Milicich, G., & Rainey, J. T. (2000). Clinical presentations of stress distribution in teeth and the significance in operative dentistry. Practical Periodontics and Aesthetic Dentistry, 12(7), 695–700.[2] Nishigawa, K., Bando, E., & Nakano, M. (2001). Quantitative study of bite force during sleep associated bruxism. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation, 28(5), 485–491.[3]Yamaguchi, H., & Tanaka, H. (2015). Bite force and occlusal contacts in patients with sleep bruxism. Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry, 113(4), 303–309[4] Oral splints for patients with sleep bruxism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. (2022). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2, CD005511[5] Liu, Z., Jiang, W., Wang, J., Xu, W., Xie, Y., & Wang, X. (2019). Effect of occlusal splints on stress distribution in the temporomandibular joint and associated structures: A finite element analysis study. BMC Oral Health, 19, 188 [6] Smardz, J., Martynowicz, H., Wojakowska, A., Michalek-Zrabkowska, M., Mazur, G., & Winocur, E. (2023). Comparison of three occlusal splints for the treatment of sleep bruxism: effects on neuromuscular and occlusal parameters. BMC Oral Health, 23, 168

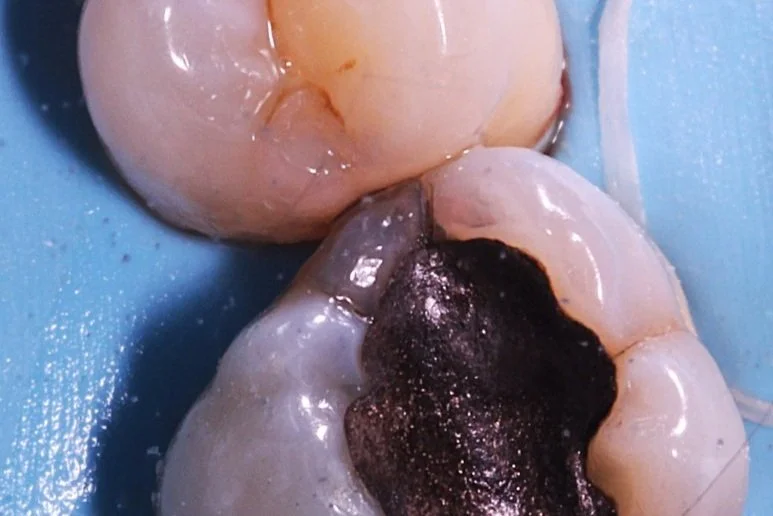

Unbonded Restorations

Cracks in a restoration with unfavorable force distribution.

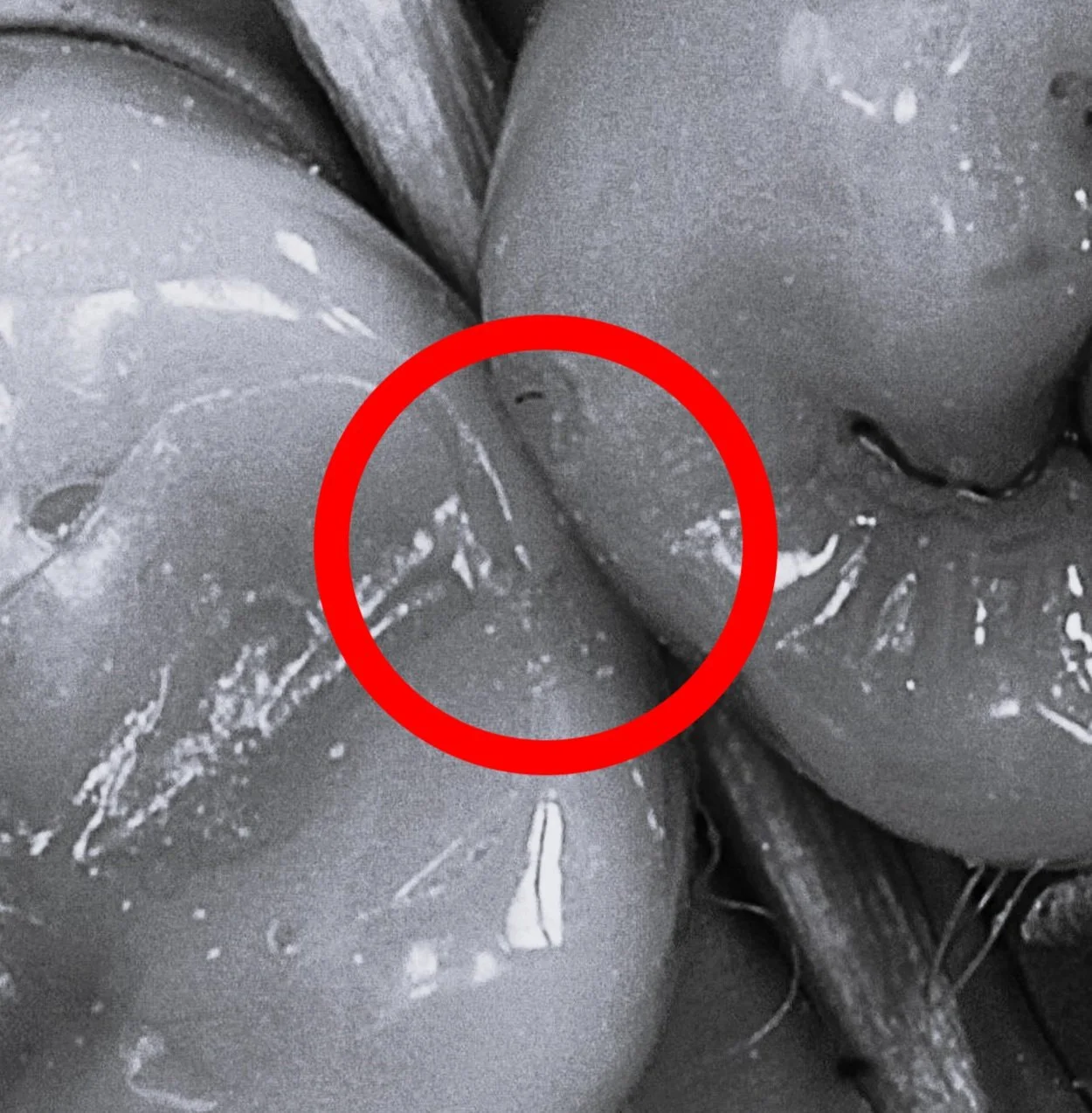

Bonded Restorations

Cracks in a restoration with unfavorable force distribution.